There have been many responses, but I would like to focus on one over at Angry Bear that captures the worst of the criticism.** The writer goes way over the top in criticizing Erdmann, saying that people who oppose the minimum wage “apparently believe that the business cycle never impacts teen employment or unemployment.” To read this article, you’d think think that the only opposition to the minimum wage came in blog-post form. Frankly, no empirical analysis coming from a blog (including Angry Bear) can offer anything but a prima facie case for or against some proposition. I don’t read Erdmann as claiming that his little graph is the final word on the minimum wage.

The Angry Bear post goes on to use some very questionable econometrics to show that the minimum wage doesn’t have a big impact on teen unemployment. The author doesn’t use the inflation-adjusted minimum wage in his graphs (and presumably in his regression) for reasons unknown, making them pretty irrelevant. He then naively regresses the teen unemployment rate against adult unemployment, a recession dummy, the teen population, and the minimum wage to find that (surprise!) the minimum wage doesn’t have a big effect on teen unemployment. For someone who criticizes others about omitted variables, this regression should be pretty embarrassing. That’s time-series data! You don’t just apply OLS regression to time-series data. OLS regression assumes uncorrelated error terms, and the fact that adult (and teen) unemployment last month is highly correlated with adult (and teen) unemployment this month destroys that assumption.

To put it in layman’s terms, this statistical technique would find any two things that trend over time to be highly significantly related. It’s not a great way to do econometrics.

That said, I think if the author of this post had used good econometrics, he still would have found little connection between the minimum wage and teen unemployment. The economy is big and complicated, and it’s nearly impossible to distinguish real causal connections between economic variables from spurious correlations and white noise. Minimum wage hikes are typically small, so it’s hard to tease their effect out from all the other things going on.

Given that it’s so hard to get anything out of the data, the winner of any empirical argument is nearly always going to be determined by our assignment of the burden of proof. If one side says “A causes B” and the other side says “A does not cause B,” then the former side will win if the burden of proof is on the latter side, and the latter side will win if the burden of proof is on the former side. If the burden of proof is shared equally by both sides, the one that says “A does not cause B” will probably win, because teasing out the effect of any A on any B is very difficult without the opportunity to conduct controlled experiments.

I can think of three reasons why the burden of proof should be on the minimum wage law’s proponents to show that it has positive effects:

- Economic theory clearly implies that the minimum wage reduces opportunities for low-skilled workers, not only because it makes it hard for them to get a job, but because it prevents them from having a full range of contracting options with their employers. Minimum wage proponents need to justify their position with strange assumptions like monopsony in the market for low-skilled labour or efficient rationing. Weak theoretical arguments should require strong empirical backing to be taken seriously.

- The minimum wage law is a case of the political class overriding the decisions of millions of workers and employers engaging in peaceful contracting. In general, when a third party such as the government steps in to override other people’s decisions, the third party should provide a good reason for its meddling. Without this presumption, we would quickly descend into totalitarian rule.

- If the proponents of the minimum wage are wrong, the burden falls on the poorest members of society. If other anti-poverty programs fail, such as those programs that just give money to the poor, the burden is on the taxpayers who paid for the ineffective program. Taxpayers are richer than those who could be unemployed by the minimum wage law, so it’s better that they should bear the risk. (This argument was made recently by Janet Neilson.)

There are my arguments. I leave it to minimum wage proponents to prove that the minimum wage should exist. Until then, I will happily oppose it.

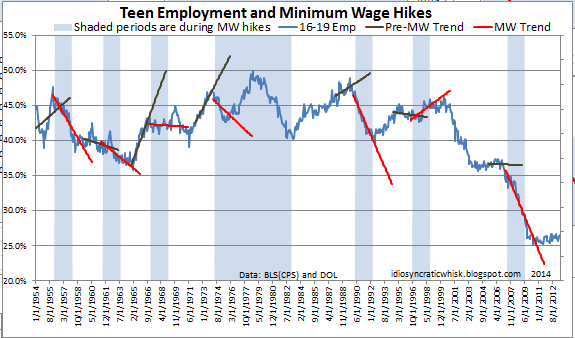

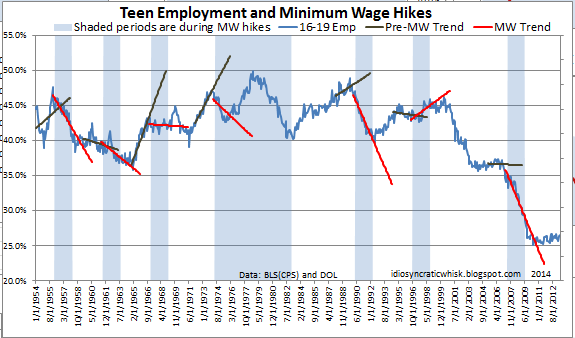

* This graph was added in a later update. Erdmann realized that the teen employment to population ratio was a more relevant variable than simply teen employment.

** Kevin Erdmann’s follow-up post deals with many of Angry Bear’s complaints. He also responded directly to the Angry Bear post in a comment on Marginal Revolution.

The post Erdmann, Empiricism, and the Minimum Wage appeared first on The Economics Detective.

Can you imagine a news article with that title? Certainly not. How about this one:

Can you imagine a news article with that title? Certainly not. How about this one: