Someone on Quora was wondering whether Murray Rothbard was a good economist. I obliged with an answer:

Yes. Murray Rothbard was a prolific thinker whose contributions to economics were numerous, original, and significant.

His magnum opus, Man, Economy, and State, was the first complete treatise on economics in a half century. The book was originally meant to be a textbook version of Mises’ Human Action, but Rothbard built on Mises’ work to create a more complete body of thought. He contributed his own theory of production and supply, while critiquing Mises’ theory of monopoly as a static conception that did not fit with his generally dynamic view of the economy. Rothbard argued persuasively for a return to the original definition of a monopoly as a government grant of exclusive privilege.

His work in economic history is excellent. His book, The Panic of 1819: Reactions and Policies is the definitive work on the titular panic. America’s Great Depression applied Mises’ theory of the business cycle to the Great Depression, showing how the Fed under Benjamin Strong pumped up an inflationary bubble in the 1920’s, which led to the 1929 crash. He also demonstrated that Herbert Hoover was not a laissez faire President but a big-state interventionist, in opposition to what was commonly (and wrongly) believed at the time.

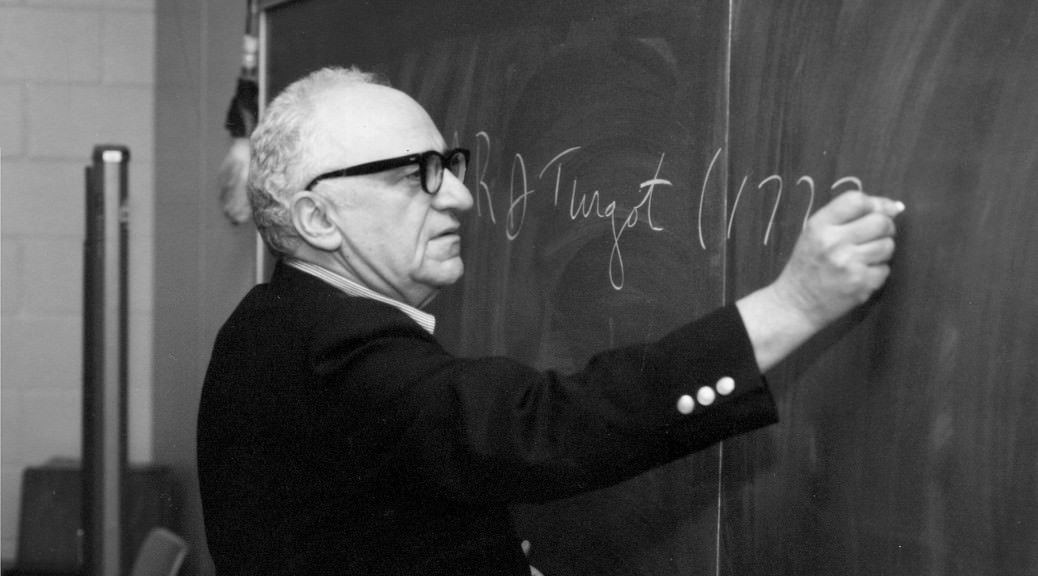

An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, Rothbard’s two-volume work on the history of thought, is by far the most exhaustive history of economic thought up to 1870 (he tragically died before he could write a third volume covering the developments after 1870). While most histories of economic thought focus on a few key figures, maybe Smith, Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, Marx, and Keynes, Rothbard covers everyone. If someone had a passing thought about economics before 1870, and it came down to us in print somehow, Rothbard probably discusses it. While most histories of economic thought will treat Adam Smith as the inventor of the discipline (maybe with a passing nod to the French Physiocrats), Rothbard spends over 500 pages discussing the economic thinkers who preceded Smith, beginning with Aristotle. It turns out that economics had a rich history before Smith, and some earlier thinkers (Turgot and Cantillon) even surpassed Smith in many respects. Even if you disagree with Rothbard on absolutely everything else, he deserves credit for being an outstanding historian of economic thought.

The post Was Murray Rothbard a Good Economist? appeared first on The Economics Detective.