I’m in the second year of my PhD, and I’m working to develop a research program; hopefully one that gets me a finished dissertation as soon as possible.

I’m drawn towards studying education because (1) I have spent my entire life in schools and (2) schools are seriously, and obviously, messed up. The marginal benefit of an additional perspective on education could be very high if that perspective were to shape education reform in some way.

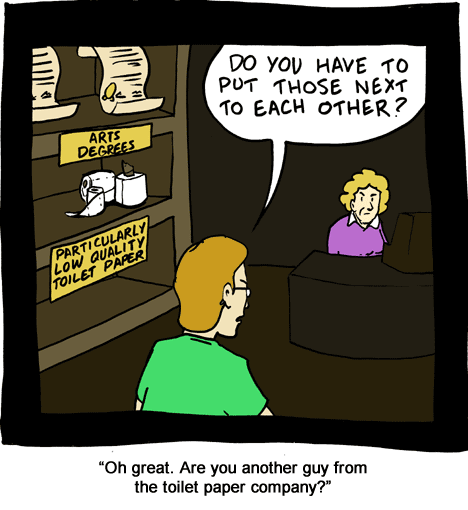

It’s a cliché to make fun of “soft” degrees, so I’m surprised there isn’t a large body of research on why people choose to pursue them anyways. However, there is a body of research on why people fail to treat education as an investment more generally, as detailed in the working paper “Behavioral Economics of Education: Progress and Possibilities” by Lavecchia, Liu, and Oreopoulos. To avoid typing out Lavecchia, Liu, and Oreopoulos many times, and to make it seem like I’m periodically pausing to laugh, I will refer to them as LOL.

LOL use the dichotomy of “system 1” versus “system 2” thinking. System 1 is the unconscious, mostly automatic part of our brains that says “Don’t get out of bed, it’s warm and nice here and getting to work on time isn’t so great anyways.” System 2 is the part that rationally deliberates our long-term choices and says “You need to get up and go to work because working yields the following long-term benefits: (1) wages, (2) the promise of future wages, (3)…” LOL include the obligatory footnote saying that neuroscientists dispute whether this is actually what the brain is doing, but go on using the dichotomy anyways because it’s an extremely useful way to organize our thinking about the brain even if that’s not how it literally works.

Within this framework, the question is why so many people allow system 1 reasoning to dominate their educational choices and not their more careful and reflective system 2. Why don’t people treat educational choices as investments? LOL see four major implications of the two systems model: “(1) some students focus too much on the present; (2) some rely too much on routine; (3) some students focus too much on negative identities; and (4) mistakes are more likely to occur with many options or with little information.” (p. 7) I’ll summarize them in order.

(1) is the quintessential result from behavioural economics: people are present biased. Economists call it “hyperbolic discounting.” The classic experimental result has you ask people to choose between $10 now and $25 in a month. Then you get them to choose between $10 in two months or $25 in three. If people’s time preferences were consistent across time, they would make the same choice each time, but since they are present biased, many people will choose $10 in the first case and $25 in the second. You can see present bias in many contexts, for instance in the retirement savings literature, where a “majority of [people] say they plan to start saving soon, yet fail to follow through with those plans (Choi et al., 2002).” (p. 9) And since young people are particularly prone to hyperbolic discounting and young people are the ones making educational decisions, it’s pretty clear that this is a major issue.

The idea behind (2), students’ over reliance on routine, is that students need to break the routine they’ve lived with their whole lives in order to, for instance, move away from home to attend university. Routine makes our lives easier by making the repetitive aspects of life easier to deal with. Think of it as system 1’s autopilot feature. So long as you keep doing the same thing every week, it becomes less mentally taxing. However, if people are averse to breaking routine, it could keep them from making potentially beneficial life choices.

When you’re relying on routine, you tend to only use readily available information. Seeking out new information, such as information about scholarships and funding options for college, requires a break from routine. Thus, even when information is available freely online, we see people ignoring it. “To give one example, Hoxby and Avery (2013) find that bright students from disadvantaged backgrounds often fail to apply to selective colleges that have lower out-of-pocket costs than less selective schools they know about. This occurs despite the fact that information about various schools, programs and costs is available freely online.” (p. 12)

So how about those “negative identities” mentioned in (3)? The general theme here is that students weight present concerns overly highly over future concerns, and perhaps the most pressing present concern for most young people is the esteem they get from their peers. Thus, when deciding how much to study, a student doesn’t just weigh the cost today of studying against the benefit of higher grades, he is more concerned with whether a given amount of effort is consistent with others in his social group. I hung out with the nerds in high school (surprise, surprise) and was fairly studious. Was it my nerd self-image that made me study, while someone else’s affiliation with the stoners or jocks made them study less? I find that plausible. Certainly some students have reason to worry that they will lose the esteem of their social group if they start studying more than their friends.

And finally, (4) tells us that complicated decisions are hard to make. For non-economists this might seem too obvious to need stating, but the baseline assumption in economics is that people make optimal choices. Neoclassical agents don’t get flustered by an overabundance of options, but humans do. “Experimental evidence suggests that when presented with more choice, savers are more likely to choose the default option even if that option may not best suit their individual circumstances.” (p. 16)

In a world populated by neoclassical agents, people would exploit all available opportunities until they equalized the marginal benefit of each potential activity. Thus, the marginal engineering student would be (virtually) indifferent between studying engineering and pursuing his next best alternative. Any remaining differences between the earnings of different fields would reflect the rents to workers’ underlying qualities or compensating differentials. We would expect particularly pleasant jobs to pay less than particularly unpleasant ones to induce people to do unpleasant jobs.

This theory is extremely hard to refute, almost to the point of being unfalsifiable. If someone makes a choice that earns him less money, he could easily be choosing to earn less money to pursue some other goal instead, such as a more enjoyable career. Even if he later says he regrets his choice, we can’t be sure it wasn’t rational at the time. Anyone who buys a lottery ticket will regret the choice if he loses. The question is whether the risk was acceptable before he knew the ticket was a loser.

However, there is one way to falsify the neoclassical theory: attempting to “nudge” the decision maker. If a decision maker is choosing rationally then making irrelevant changes to the decision, like changing the default option or giving him information he could already access, should not impact his choice. Where the behavioural economics literature excels is in showing the efficacy of a wide variety of nudges, thus falsifying the (strong) neoclassical assumption of rationality.

Jensen (2010) is a classic in this literature. He told some randomly selected children in the Dominican Republic about the difference in earnings between people with different levels of education, and the students he told about these differences were 4.1 percentage points more likely to enroll in school for grade 9, and completed 0.2 additional years of school on average. Pretty impressive for just giving kids a bit of information.

Since I am interested in people’s choice of degree, I was intrigued by Harackiewicz et al., 2012., which mailed high school seniors’ parents with information about the advantages of STEM courses. The students whose parents received the package enrolled in nearly one more semester of STEM courses on average. Interestingly, the effect was largest for the children of college-educated parents, perhaps because these students were more likely to have the prerequisite math and science courses at the high school level. I’d like to see an inverse study where they pick a few of the least remunerative majors and mail out information on how many of the people who majored in them ended up as line cooks and salespeople. That would get parents’ attention.

However, nudges don’t always work. Kerr et al. (2014) randomly assigned a portion of 3500 graduating Finnish high school students to attend an information session on the relative earnings of different degrees. The null hypothesis came out swinging: There was no difference in the application and enrollment behaviour of the treatment and control groups.

Why does telling kids in the Dominican Republic about earnings differences make them change their behaviour, while telling Finnish high school seniors doesn’t? Well, the Finnish information session might have been particularly boring and easy to ignore, or maybe Finnish students are just particularly diligent at applying earnings information with or without an info session. Or maybe since Finland has high progressive taxes and a 24% VAT, people just rationally weigh other considerations above earnings.

If I may speculate based on my experience, it seems that wealthy, Western millennials have a fairly unique attitude towards education. I am the only Canadian in my PhD cohort, and the only other Canadian PhD student in the department is a 5th-year student about to go on the job market. About 75% of the PhD students are from China and Iran (our department has a special relationship with the University of Tehran) and when I teach undergraduate tutorials I am usually the only non-Chinese person in the room. I once wondered aloud where all the Canadians were, and my friend Ricardo (a Brazilian PhD student) said, “They all majored in art!”

That rings true. When I told the people in my academically strong Canadian high school that I wanted to study business (before later switching to economics), I would get strange looks. One person said, “Oh, I don’t care about money.” That was the dominant attitude: people really cared about signalling their distaste for bourgeois careerism. They wore their intention to major in art or creative writing as a badge of honour, a sign that they were willing to live a life of noble poverty to pursue the finer things in life. I think this might count as one of those “negative identities” mentioned by LOL, though it isn’t as clearly negative as “I am stupid so I shouldn’t study.”

Every time I met someone during my undergraduate days, my first question would be “What’s your major?” So much of how us wealthy, Western millennials perceive each other is tied up in that question, so it’s no wonder that we treat our educational choices as a means of expressing our individuality, not as an investment. Even those of us who majored in harder subjects like econ viewed ourselves as contrarian and outsiders, and reveled in our identities as hard-nosed, serious people. We bought into the same “major as identity” attitude as the art majors did.

However, the underemployed art majors of yesterday don’t hold the rosy “noble poverty” view of soft degrees. My experience working in an opera house during my undergraduate years exposed me to the fine arts, graphic design, and English degree holders who stayed underemployed after their degrees. My manager told me that before the Great Recession, people would work in the theater for a few years, finish their degrees, and then go on to jobs in their fields. Post-2008, the seniority list used to determine shift allocations crystallized: people stopped finding jobs in their field and they stopped leaving. My sister had a similar experience working in a restaurant. I think part of the reason this more cynical attitude has trouble trickling down to the high school seniors and undergraduates who are making their educational decisions is our radically age-segregated upbringing: We spend our early years in schools where they divide us up into age cohort, where we have very little interaction with those five or six years older than us. LOL say that people tend to overemphasize readily available information to inform their choices. Could it be that the age-segmentation of society turns the real experiences of older age cohorts into distant, abstract information? If we had daily interactions with people older and younger than we are, maybe we’d have an easier time acting on the information embodied in older cohorts’ experiences?

Unlike wealthy Western millennials, the immigrants I’ve met are much more serious about getting a payoff from their educational investments. If you’re from China, India, or Iran, poverty is not a relic of the distant past for you. You can’t afford to sneer at bourgeois careerism because you know what real poverty looks like and you have no illusions about it.

So here are some hypotheses based on my wild speculation:

- Wealthy Western millennials neither know (much) about nor care about the relative earnings of different degrees. Telling them about these earnings differences would have little effect on their behaviour.

- Wealthy Western millennials do not know about, but would care about, the underemployment rates of different degrees. If they realized that they had a high likelihood of not working in their preferred field at all, those on the margin might switch to more employable fields.

- Immigrants know (or implicitly know) and care about the relative earnings of different fields. They will respond to better information about earnings differentials by changing their behaviour, but only to the extent that their prior beliefs were incorrect.

- Immigrants know (or implicitly know) about the underemployment rates of different degrees

Here’s how I would go about testing these hypotheses: First, create two surveys, one asking students what they think different majors earn, and one asking them what they think the underemployment rates of different majors are. Survey a large number of 1st year students, with one survey or both, and link their answers to administrative data. Randomly select a portion of the survey respondents and email them a link to a page telling them how accurate (or inaccurate) their answers were. Keep track of who clicks the link and who doesn’t. Check back in a few years (using the administrative data) to see whether anyone changed their educational choices. Segment all the results by students’ country of origin.

The nice thing about this is that I can get two papers out of it, one on the results of the survey and one on students’ educational choices. The downside is that surveying a load of students will be costly and difficult. Also, getting access to administrative data means jumping through a lot of bureaucratic hoops; they don’t just give that private information to anybody. Furthermore, if I want to tell students whether their answers are accurate, I would need access to survey data about the earnings and employment status of graduates. How diligently does my university keep track of such things, and how willing will they be to share it with me?

Still, that’s my plan and I hope it all goes well. I’ll let you know in a few years whether I actually followed through with it.

The post Thoughts on the Behavioural Economics of Education appeared first on The Economics Detective.