Classical liberals like Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek have supported the idea of a basic income guarantee as an improvement on the current patchwork of welfare programs. The welfare systems in most countries are the product of a century of piecemeal reforms, where politicians have created many overlapping programs targeting different problems and interest groups. This makes perfect sense from the politicians’ perspective; creating a new program allows one to attach one’s name to a high-profile bill, thus winning favorable media attention and votes. It’s the same reason governments often create shiny new highways rather than filling in the potholes on old ones. Where’s the glory in marginally improving something with someone else’s name on it?

As a result of this political process, welfare systems have dramatically higher administrative costs than they need to have. Rather than having separate (and often multiple!) bureaucracies to administer welfare programs for the homeless, the temporarily unemployed, seniors, disabled workers, single mothers, etc., why not fold them all into one? In fact, Milton Friedman’s negative income tax would fold them all into the agency responsible for administering taxes. Replacing a hundred parallel agencies with one agency tasked with administering a simpler system would clearly reduce overhead costs.

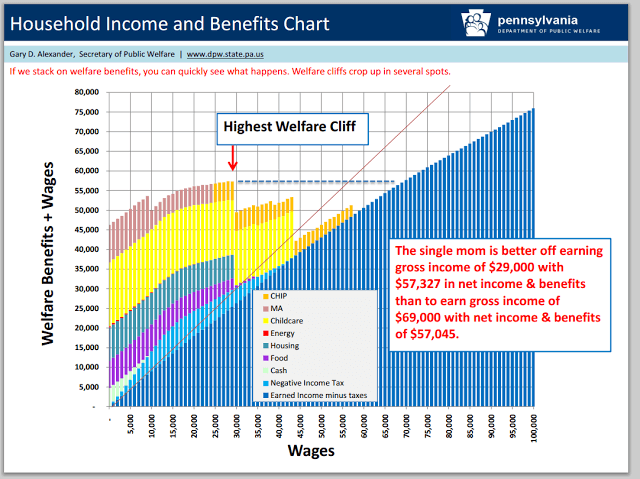

The other consequence of the patchwork welfare system is that it creates more severe unintended consequences than it needs to. All redistribution schemes affect incentives, but a basic income guarantee paired with a reasonable tax scheme (maybe a flat tax or a progressive consumption tax) would avoid the worst of the perverse incentives. Current welfare systems feature “welfare cliffs,” where many programs abruptly cut off at the same income level, leading to absurdly high implicit marginal tax rates. The examples I’ve seen have situations where earning $1,000 more income can make one ineligible for $10,000 in benefits from various programs. That’s an implicit marginal tax rate of 1000%, far higher than the tax rate paid by the highest of high earners!

Since a basic income guarantee is a lump sum paid to all citizens, it doesn’t have this feature. Marginal tax rates still have to be positive to pay for it, but they would never be higher than 100%.

This all sounds great so far, but as David Henderson points out, the math doesn’t really check out. The way the basic income guarantee is typically sold implies that we could replace current welfare programs with a basic income guarantee and remain revenue neutral.

Here are some back-of-the-envelope calculations to show this wouldn’t work. I’ll look at the Canadian case because I live in Canada, but the results should be similar for other developed economies.

As of the 2013-2014 fiscal year, the Federal Government of Canada spent $72.2 billion on transfers to individuals (including old age security, employment insurance, childcare benefits, etc.). At a population of 35.5 million, that comes out to just over $2000 per person per year. Not enough to live on. I’ve heard proponents of the basic income use $10,000 per person per year as an estimate of how high the basic income would have to be, so calls for a basic income to replace other welfare transfers amount to calls to expand government transfers by a factor of five.

The Basic Income Guarantee Can Replace More Than Just Welfare

Canada and other countries can have a revenue-neutral basic income if we realize just how many government programs are thinly veiled redistribution schemes. The biggest examples are education and medical care.

I think if you ask the supporters of public education and public healthcare why they support these policies, it’s primarily because of equity concerns. What would poor people do if they couldn’t afford education or medicine?

Sometimes you hear efficiency arguments, but a lot of them sound more like ex post rationalizations of the status quo rather than serious justifications for public provision. If you can point to a market failure present in either the market for education or for medicine, that is not sufficient to justify public provision. You also have to show that there is no feasible policy that can fix that market failure without sacrificing the efficiency benefits of markets.

So, for instance, if you think education has positive spillover effects, that justifies at most a Pigouvian subsidy to schools.

For Canada, education and healthcare cost the government about $3000 and $6000 per person per year, respectively. So that’s enough to finance $9000 per person per year of a basic income guarantee. If we abolished public schools, public hospitals, and existing welfare programs, we could pay every single person $10,000 per year for their entire lives and still have money left over.

Ask yourself if you would rather have public education, public healthcare, and whatever transfers you currently receive from the government, or $10,000 every year for your entire life.

Yes, you would have to pay for school and health insurance yourself. But we would expect the prices of both those services to fall with market competition. I know what I would choose.

The post A Basic Income Guarantee Can Work if it Replaces State Education and Medicine appeared first on The Economics Detective.