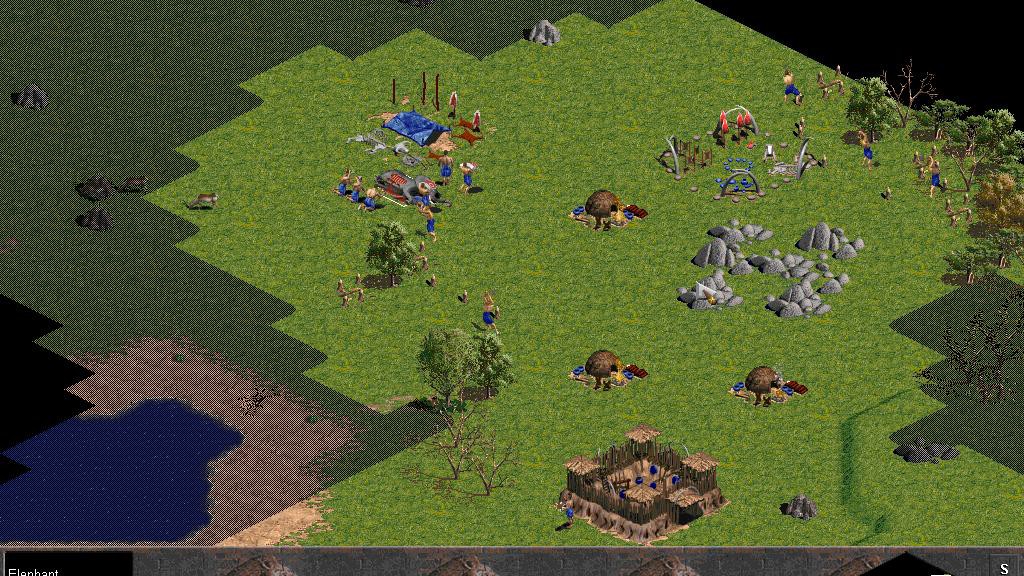

When I was young, I played a lot of Age of Empires. For those who are unfamiliar with the series, they are games where the player must direct a tiny civilization’s development. He begins with one building and only a few villagers. By right clicking on a villager, then left clicking on a tree, stone mine, gold mine, or animal, the player can direct the villager to gather wood, stone, gold, or meat. He can also direct villagers to make buildings. And with buildings, he can recruit more villagers or soldiers.

By directing every action of every person in his civilization, the player can eventually turn his tiny village into a sprawling city, clashing militarily with other players’ civilizations.

I think a game economy like that one could be a good teaching tool for young people. In the early stages of the game, centrally managing a few villagers works well. But as the civilization grows, the player’s attention becomes more stretched. It is common, in the game economy, for the player to discover a group of villagers clustered around a (now exhausted) mine or forest. The growing economy becomes ever more difficult to manage, and it becomes more difficult to coordinate the growing numbers of workers and soldiers.

In the game, the complexity cannot grow without limit. The computing limits of the day meant the game had to cap the population at about one hundred tiny people. Furthermore, the production processes allowed anything to be created from wood, food, gold, stone, and villager labour. In a real economy, these would expand into ever more complex and roundabout processes as the economy continued to grow.

Nonetheless, a game like Age of Empires is a good demonstration of how the difficulties of central planning compound as an economy grows in size and complexity. What remains is an explanation of the alternative: an economy where each of those villagers decides for himself whether he will chop wood, mine stone, mine gold, or hunt deer. Sadly, I don’t know of too many games that show how private property and prices can coordinate the actions of disparate individuals. There are plenty of business simulators, but these only show the activities of a single businessman, the player, and sometimes his competitors.

But maybe games aren’t the right place to look for examples of spontaneous order. The place to look for spontaneous order is the real world. Ask young people who have played Age of Empires (or similar games) what the difference is between the game economy and the real economy. They told each person in the game economy whether to be builders or miners or hunters; who in real life directs each person into an occupation? Nobody, at least under capitalism, performs this role. Each person decides for himself what job to apply for given the wage he thinks he can earn. Point to one of those clusters of workers around a long-since-exhausted resource. Ask the young people what the owner of that resource would pay to have people work there, even after it has been exhausted. Clearly he wouldn’t pay anything, so those workers would look for other jobs. Thus, if those workers had the free will to decide what to do for themselves, they would not be wasted waiting for the central planner (i.e. the player) to tell them what to do.

In my education, I was never told about the way people coordinate through prices until I saw someone draw supply and demand curves in an undergraduate classroom. But ultimately, these concepts are not too difficult for people to grasp at young ages. You don’t have to get into difficult, technical debates to show that prices reflect scarcity and people respond to prices, so people respond to scarcity through prices. Age of Empires demonstrates a world without prices, so it might be a good place to start.

The post Teaching Economics: Age of Empires and Central Planning appeared first on The Economics Detective.